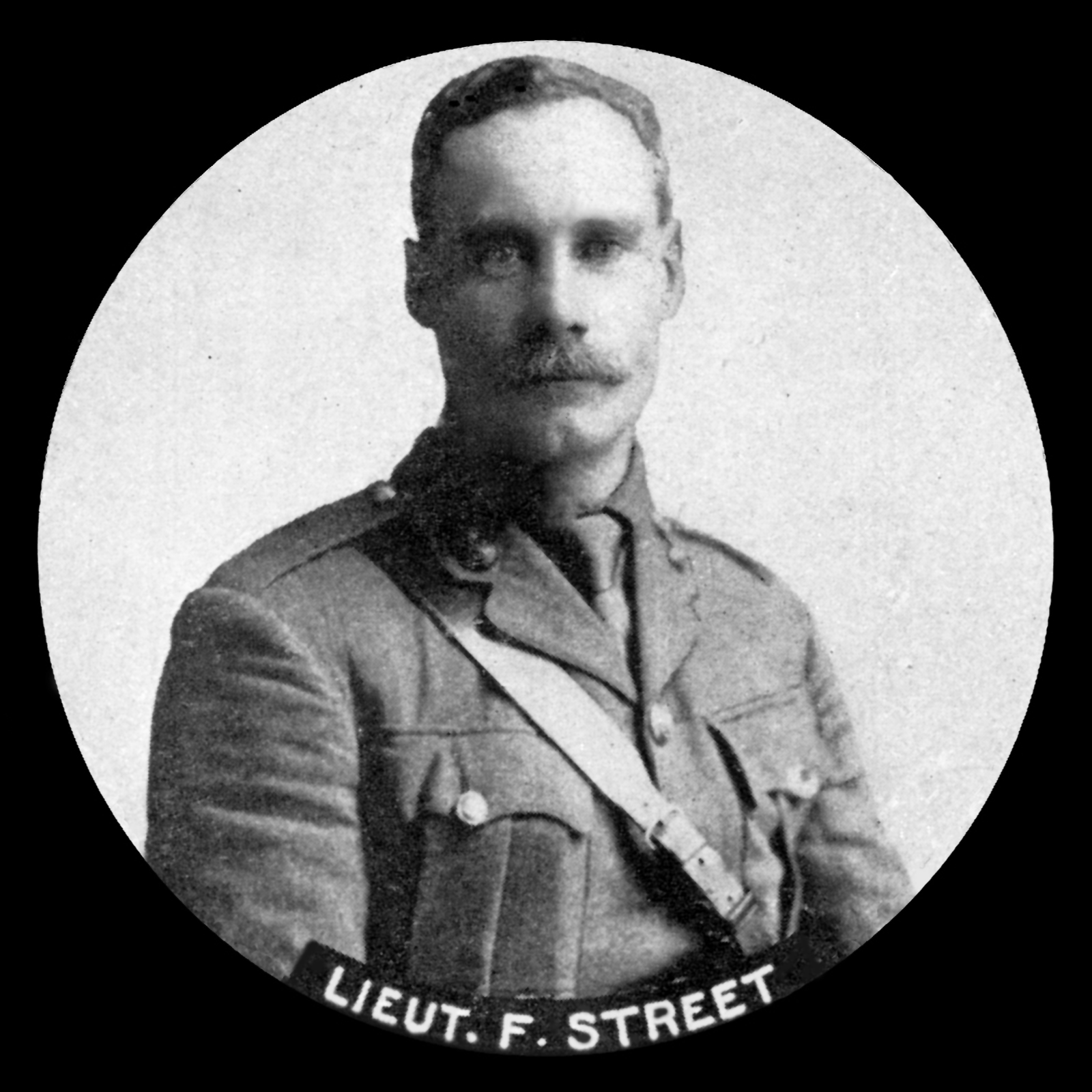

Frank Street

View Frank on the Commonwealth War Graves Commission website

Known information

Frank Street was a 44 year old married schoolmaster at Uppingham School when the First World War broke out. But he recognised that everyone was needed for the army and he immediately joined up as a Private in the 9th Battalion Royal Fusiliers (City of London Regiment). Frank, who was born at Maida Vale in London on 31 May 1870, was quickly promoted and made a Sergeant before being given a commission and becoming an officer. He went out to France on 14 November 1915 and was killed in the Battle of the Somme. On 7 July 1916, the Fusiliers, part of 36th Brigade, took part in a third British attempt to capture the strongly fortified village of Ovillers. The two previous attacks had been a disaster and Ovillers was still firmly in German hands. The attack opened with an intense British bombardment to which the Germans replied in kind. The Fusiliers, ready to go over the top in their front line trenches, suffered severely. The battalion war diary says: "There were no dugouts available and our casualties were very heavy." At 8.30am the Fusiliers attacked. The war diary recorded what happened: "A Company was decimated by MG [machine gun] fire and the same fate met two platoons of B which followed. D and C on the left were more successful and although greatly weakened, managed to reach the German trenches which they carried by assault. The enemy's fire and support trenches were captured and consolidated. Two MGs were put out of action and 50 prisoners were captured." Frank was one of the casualties that morning, killed by a bullet. Uppingham School Magazine reported: "The loss of Frank Street is one that cannot be repaired...Street was the best type of man we cannot afford to lose - the unselfish Englishman. In whatever department of life we look at him, and like most schoolmasters, he was versatile enough, the same stamp is revealed. So fine an athlete might have been allowed some conscious pride in his prowess; but love of skill, keenness for a side, were the only instincts that inspired Street. In school, out of school, in the house, boys learnt to know and admire the same examples. To his friends he never cooled as some men do when the pre-occupations of life increase. As a soldier he gave unstinted energy to a profession which was not his original choice. He achieved excellence from a high sense of duty...His failings, if such they can be called, were modesty and the lack of personal ambition...At first he doubted his military value; he felt he could serve his country best by serving the school. But he quickly saw what England took many months to realise, that most men must be soldiers until further notice...Again modesty put him in the ranks; it was loyalty with modesty that kept him with his regiment when higher rank and responsibility were to be had elsewhere for the asking. It is for us to blame our system, or the want of it, whereby better use was not made of his line qualities and high attainments, and to lament that our best was squandered too easily; but for him we feel no regrets; his life was fine, and his death a brave Englishman's. He was indeed typical English; by which one means that he was free from "swank" of any kind. He was never morose, he was never touchy, his sense of humour was ever ready. These are some of the reasons why he was so universally popular. He radiated sympathy. If one had a grievance Street got the full benefit of it. His favourite solace for the wounded soul was generally the phrase: "All right, it's a jolly good discipline"; and if that did not soothe, the patient soon forgot his little trouble by seeing its insignificance in the full light of Street's wider outlook...He loved Uppingham; and that is not merely saying that he identified himself with the institution where lay his work. He loved her history and her life...He delighted in nature and was a keen observer of bird life. A letter from his company commander tells us how, before the advance, he kept his men in hand under a heavy shell fire. We know the sort of encouragement he would have given, and almost seem to hear the words; next we see him leading his platoon over 'No Man's Land'. There the picture ends. To say more is mere vain repetition; besides a voice from somewhere seems to say: 'Oh, chuck it!' or something similar. We'll leave him there; but never a braver soldier fell, never was mourned a dearer friend. Lieutenant Street was among the first to go. Who shall say how many waverers he carried with him, or appraise the worth of such a man in such a corps. He fell a full Lieutenant at the age of brigadiers, but at the school from which he flew to arms his noble name will never die." Frank has no known grave and he is remembered on Pier 9A of the Thiepval Memorial and is remembered on Uppingham's war memorial. He left a widow, Marie Willoughby Street.

See where all our Rutland soldiers died during the Battle of the Somme on our interactive map.

|

Do you know something about Frank that hasn't been mentioned? You can add any new information and images as a contribution at the bottom of this page. |

.png)

.jpg)

Please wait